behind the frame: Marvin Gaye & a history of making art when the world is in chaos

what's going on??????

Last night, I gave my first lecture outside the walls of academia.

It went well.

I was nervous—more nervous than I expected. It was the first time I’d been hired to talk history in a gallery, the first time since “alina, phd candidate” quietly became “alina, phd” in my Instagram bio and email signature. When I asked the owner of the gallery what he was looking for in this series, he said: “You can do anything.” I thought immediately of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On.

I’m trained as a 19th-century historian, but that album has haunted me ever since I studied it in 2018. It is music, but also a message, a protest, a plea. It feels like a total work of art—Gesamtkunstwerk. And in preparing this lecture, I found myself circling the same question that animates Gaye’s music: how do artists create in times of crisis, and how does their work reshape history in turn?

I’ve made the slide deck available at the end of this essay if you are interested. There are about 50% more images there than in this substack.

Note: Due to length and images, this essay may not display fully in email. For the complete version, please view it on the Substack app or website.

In the name of context, let’s dive into the world and art of 1969-1970.

What was going on?

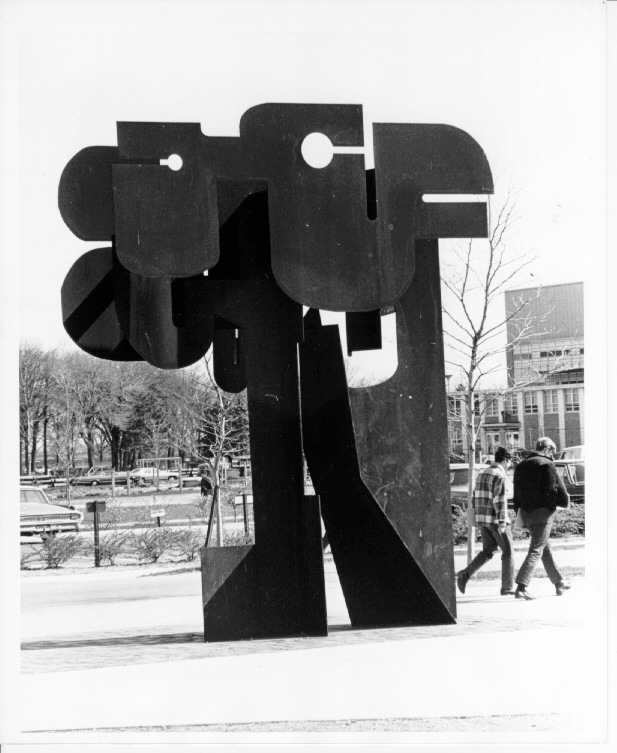

In 1967, sculptor Don Drumm created Solar Totem #1. Made of metal, it has sharp lines. The corners could cut. It was placed on the campus of Kent State University.

Three years later, President Nixon announced the Vietnam War was expanding into Cambodia. The public outcry was swift. Calls for protest spanned the US. College campuses reacted.

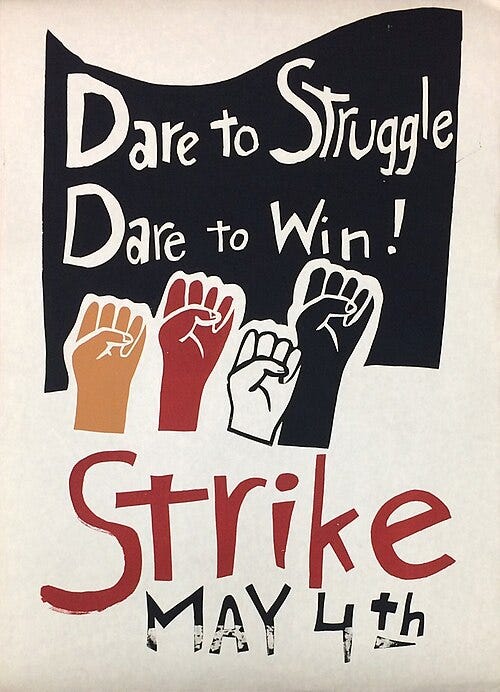

A poster from 1970 reads “Dare to Struggle, Dare to Win! Strike May 4th”.

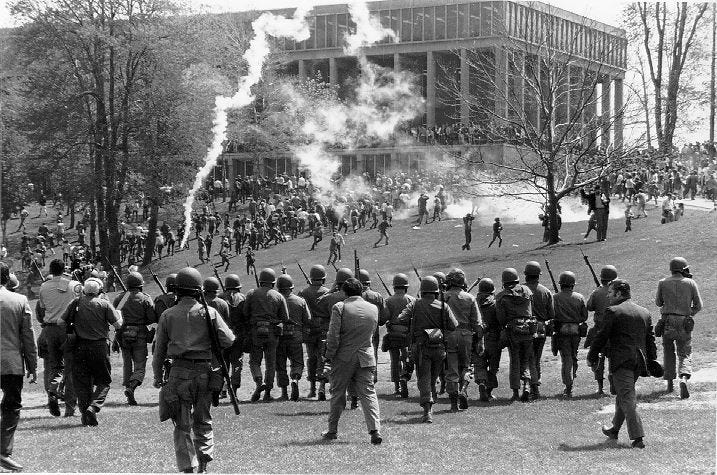

Students at Kent State protested on May 1st and called another meeting for May 4th. Tension built to the point the National Guard was sent to quell demonstrations on the 4th. They opened fire.

Four students were killed and 9 were wounded. One person was permanently paralyzed. Images from the day are haunting. Those killed were Jeffrey Miller, Allison Krause, William Schroeder, and Sandra Scheuer (Kent State.)

A stray bullet hits Solar Totem #1.

Don Drumm is asked to prove whether or not the stray bullet was from a student sniper or the National Guard based on the fraying of the metal. He and several journalists fired the same type of weapon the National Guard used into the sheet of metal. His test revealed it was fired by the National Guard, and the students were not armed with guns.

History and art were intertwined.

Protests erupted around the country. On May 5th, thousands of University of Washington students blocked an interstate highway, facing off against state troopers in riot gear. They protested both the invasion of Cambodia and the Kent State shootings.

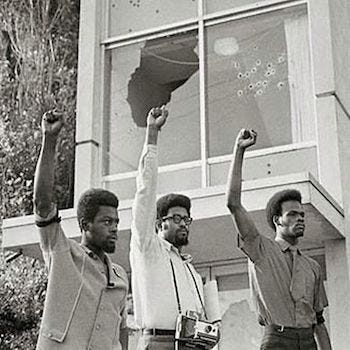

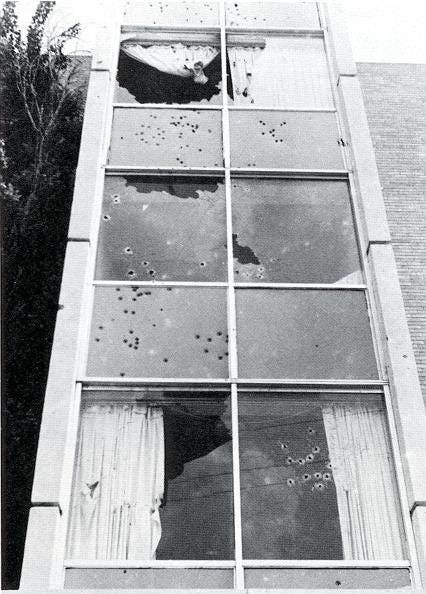

Just days later, on May 14–15, another tragedy unfolded at Jackson State College, now University, an HBCU, in Mississippi. (via Jackson State.)

This time, armed officers opened fire into a women's dormitory. When the gunfire ended, at least 140 shots were fired. Shooting lasted approximately 30 seconds. Phillip Layfayette Gibbs, 21, a junior pre-law major, and James Earl Green, 17, were dead. Twelve others were hit by the shotgun blasts.

The Gibbs-Green tragedy is overshadowed by protests over the shooting at Kent State.

Don Drumm, creator of Solar Totem #1, creates Bridge Over Troubled Waters in memory of the victims at Kent State and Jackson State. It is located on Bowling Green State University’s campus in Ohio. It is made of the same metal he used to test the ballistics of gunfire. This piece features rounded corners and circular, bullet-shaped holes.

Via Kent State:

When he designed the piece, known as Solar Totem #1, his plan was for the artwork to change with the movement of the sun, the 100 or so steel plates perpetually throwing shadows this way and that.

As it turned out, Solar Totem #1 is an ever-changing piece of art, but not in the way Mr. Drumm intended.

We make art in response to history and by interacting with it, shape and are shaped by it.

That is the major takeaway from this lecture.

—

U.S. presence in Vietnam was a major frustration during this period.

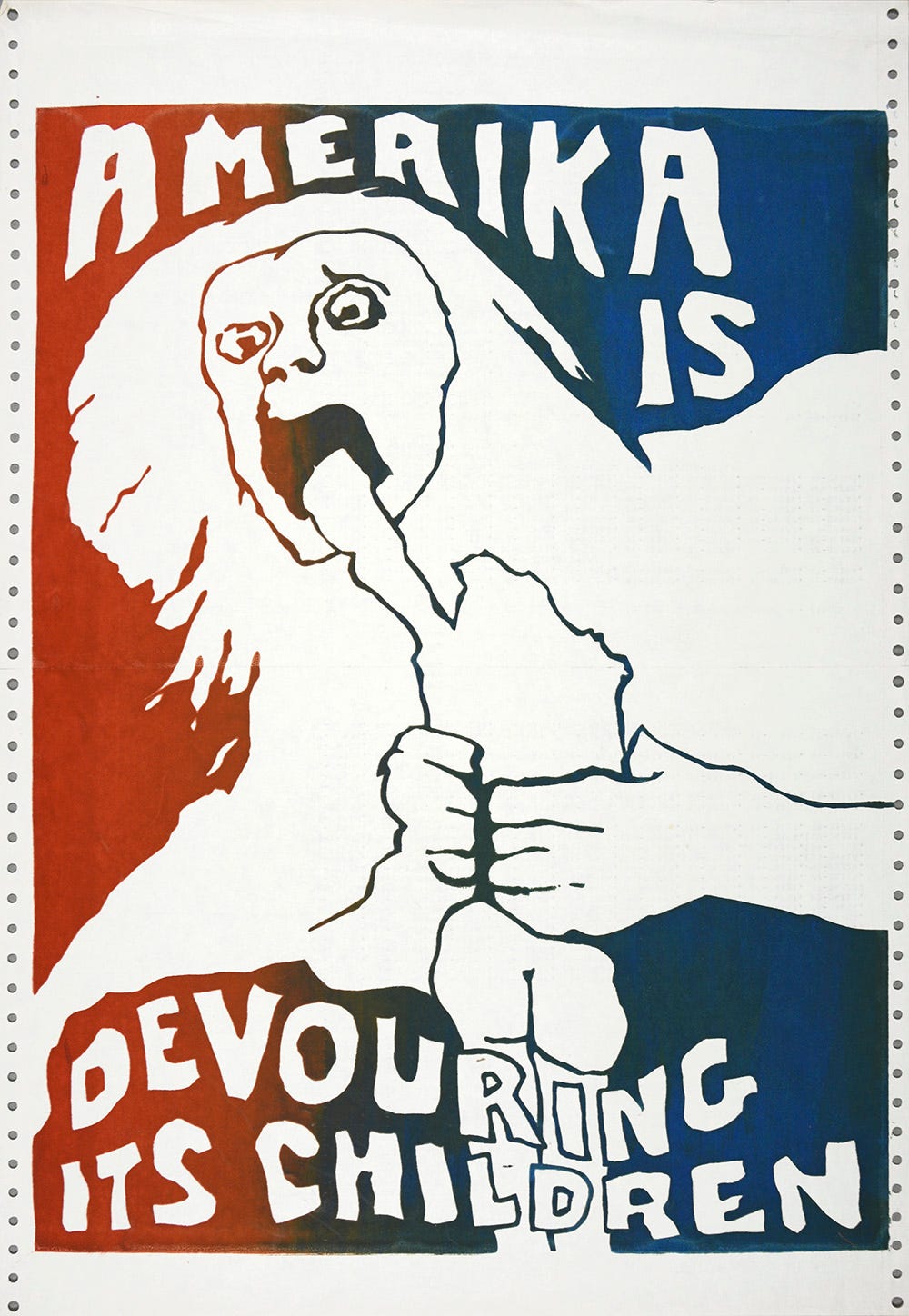

Here is a poster by Jay Belloli from 1970.

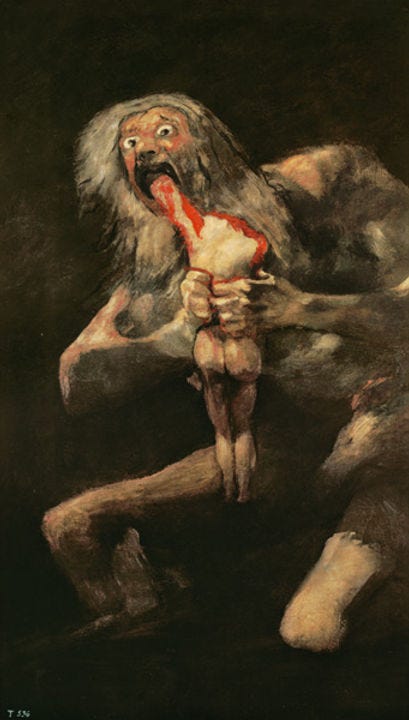

I believe they made it in a political poster workshop or seminar. It features a creature eating the form of a body and the text “Amerika is devouring its children.” The plea to get American soldiers out of Vietnam was a reference to the 1823 piece by Francisco de Goya called “Saturn Devouring One of His Sons” (Oil on Canvas)

In Austin, many protested against the Vietnam War.

Brown v Board ruled school segregation to be unconstitutional. Integration of schools frustrated many who preferred not to be bused. A photograph of children and parents participating in an anti-integration march in Clarksdale, Mississippi, suggests that by 1970, people were still frustrated with the programs.

optimism vs political reality

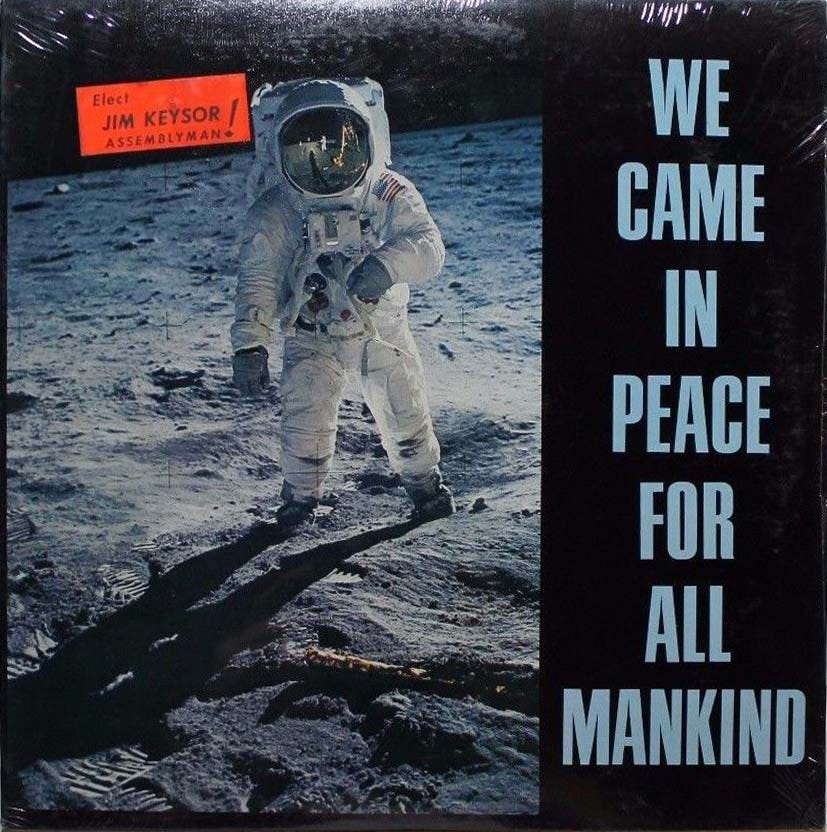

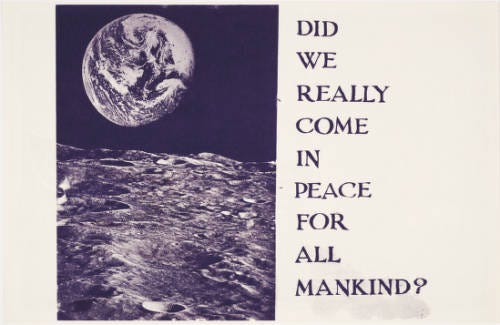

In July of 1969, the United States put a man on the moon. A plaque with Nixon’s signature is at the bottom. It states, “We came in peace for all mankind.”

Jim Keysor used the moon landing to further his political prospects. His election bid included audio of key speeches of the day. It reads in all caps, “We came in peace for all mankind.”

A political poster sought to undermine that thought. Created in 1970, it asks, “Did we really come in peace for all mankind?”

Did we?

Earth Day 1970

The first Earth Day was held on April 22, 1970.

It was founded by Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin, who wanted to bring environmental issues into the national spotlight after events like the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill.

An estimated 20 million Americans participated in rallies, teach-ins, and demonstrations across the country, making it one of the largest civic events in U.S. history.

Robert Raushenberg created posters to commemorate the day. Other Raushenberg posters feature contrasting colors, bright greens, and reds, or harsh black and greys.

AIM

The American Indian movement asked Americans to reframe their relationship to Native peoples. They asked for recognition and fair treatment.

A linocut on paper by TC Cannon featured an Indigenous man with the following text “BIG SOLDIER *X”. The X likely symbolized the mark of the individual featured.

Another poster from 1973 advocates for supporting the activists occupying Wounded Knee.

Also in the 70s, the crying indian ad featuring Iron Eyes Cody (born Espera Oscar de Corti, of Italian, not Native American descent) crying about the prospect of environmental degradation.

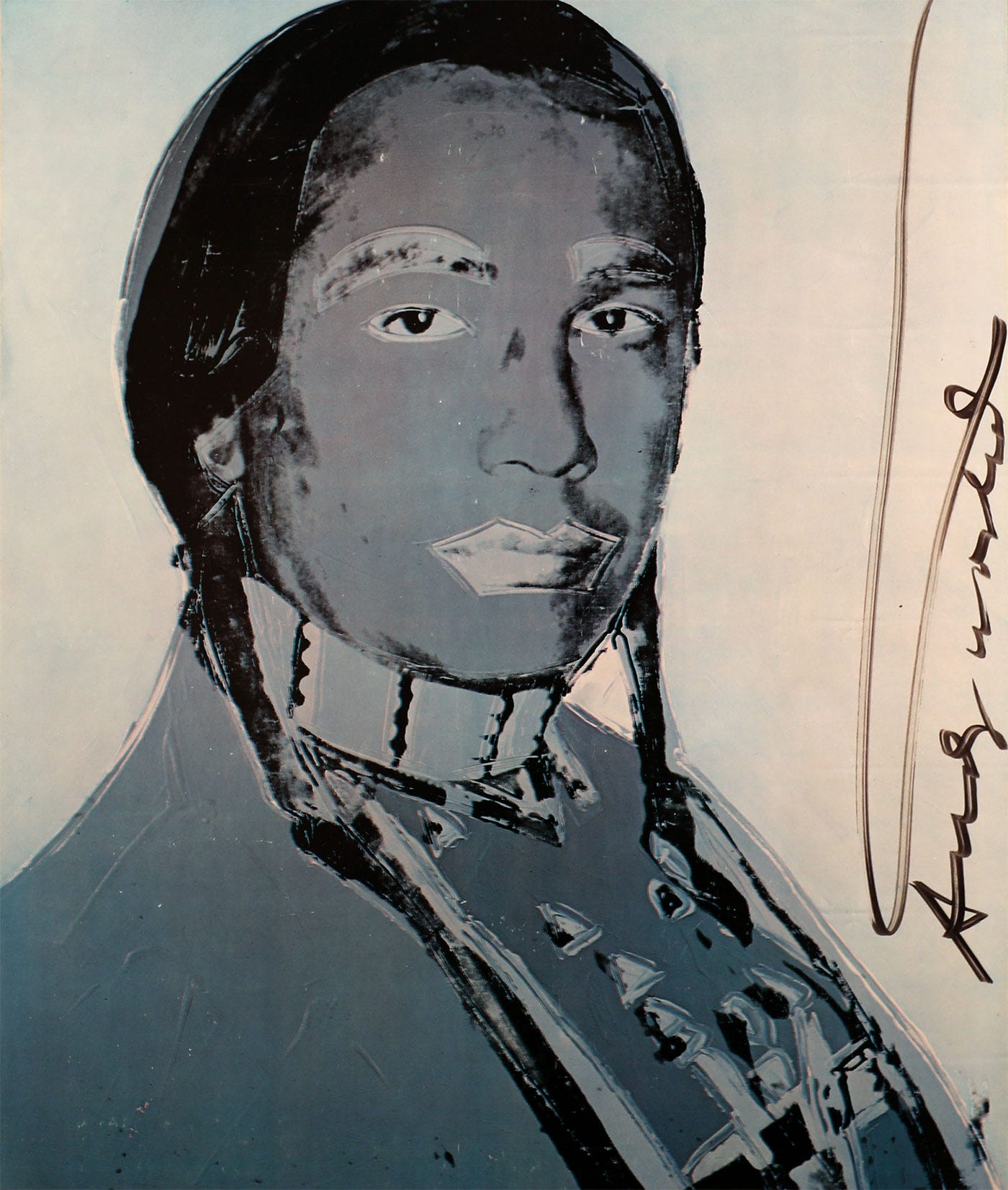

Andy Warhol creates an offset Lithograph of American Indian activist Russell Means.

Art of the Black Panther Newspaper

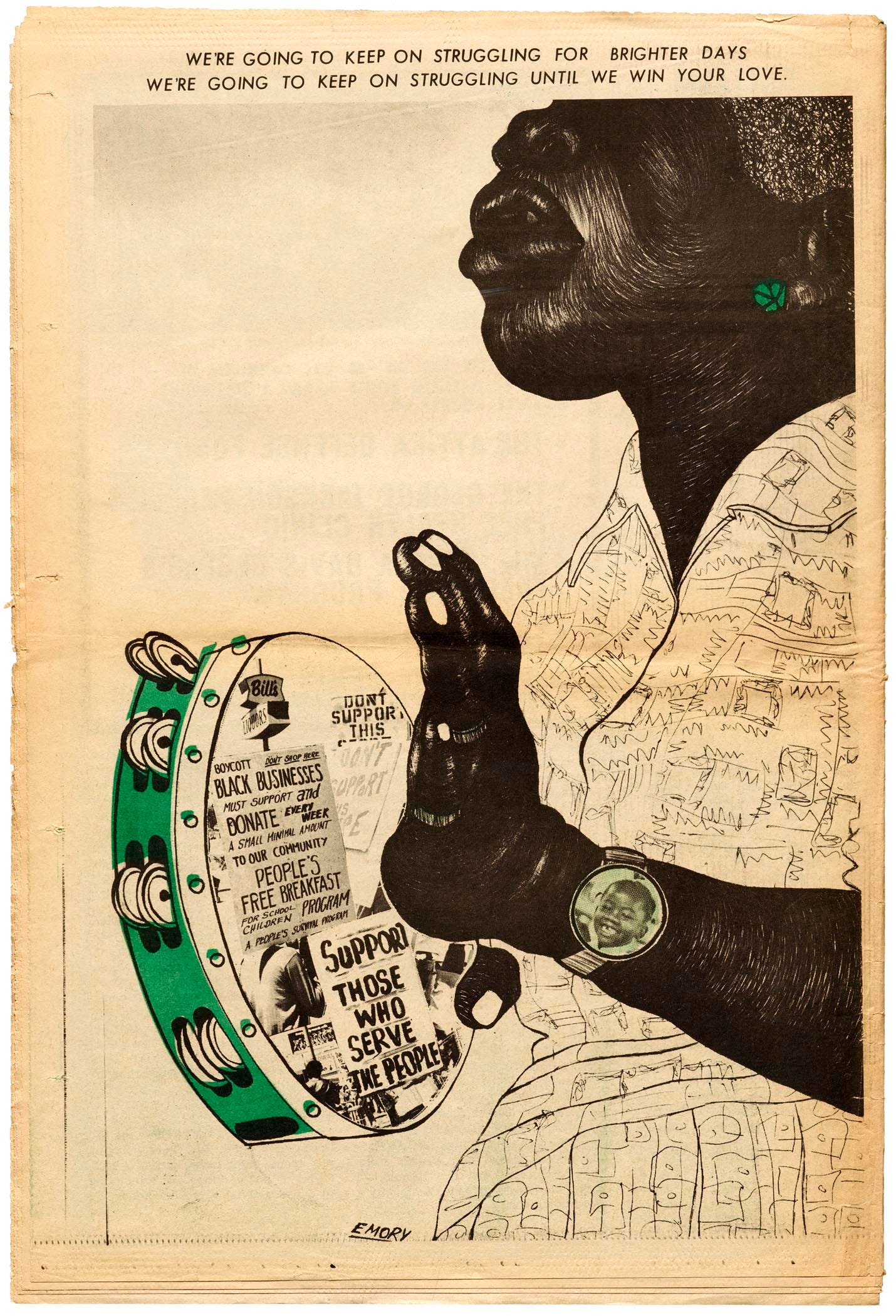

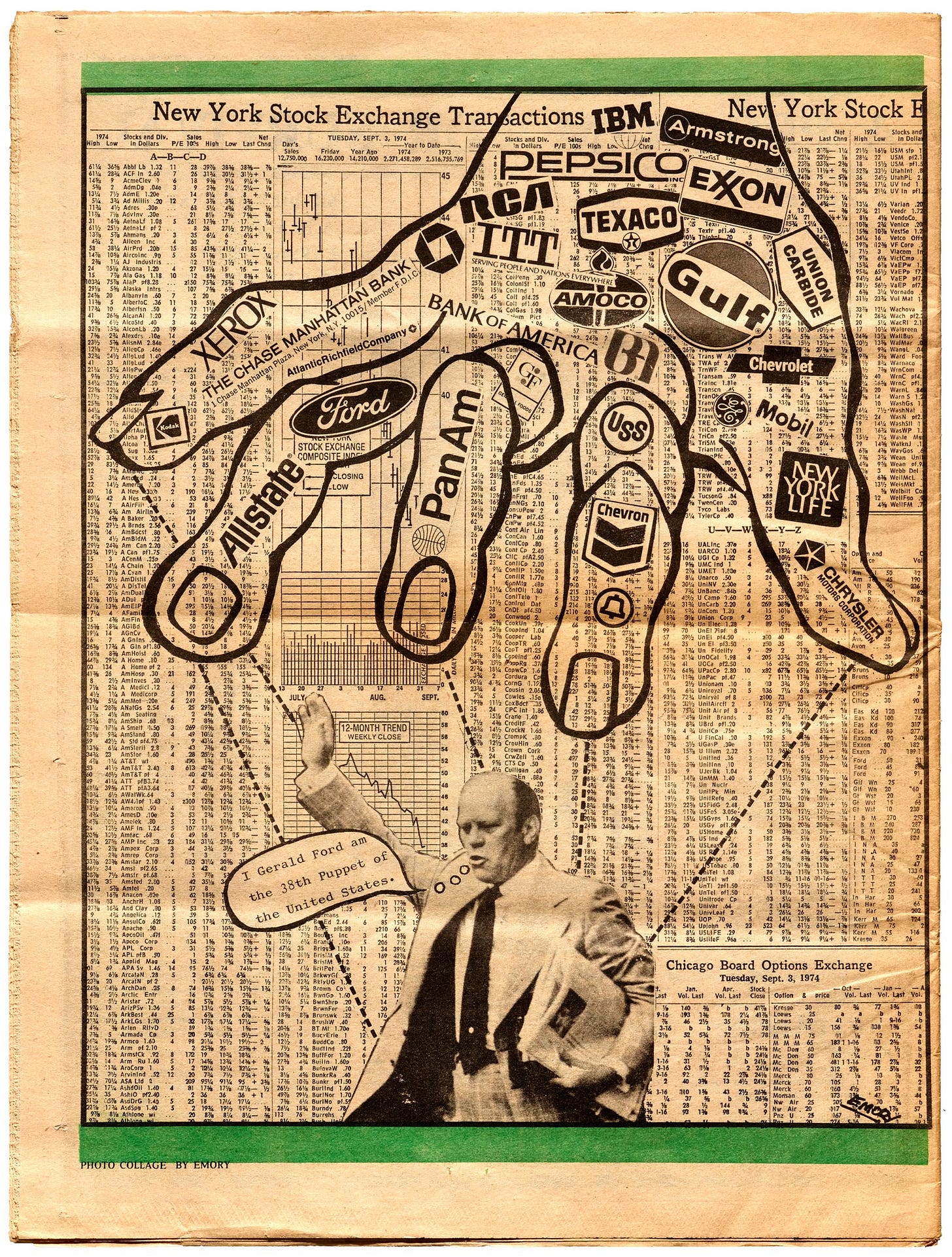

Emory Douglas, the Panthers’ Minister of Culture, filled the party’s newspaper with bold illustrations. It is pointed and direct. Uplifting and jarring.

The back cover of an edition of the newspaper “Support Black Businesses,” “Donate” “People’s Free Breakfast” “Support those who serve the people.”

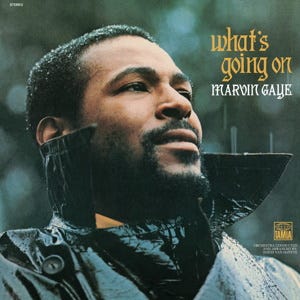

Marvin Gaye’s Total Work of Art

It is in this context, Marvin Gaye produced What’s Going On. His brother had returned from Vietnam scarred and different. His longtime singing partner was ill. And Motown shelved it. It is possible it didn’t pass the quality control stage of production at the company.

Some sources suggest he told leadership he would make no more music for them until they released it.

He produced the title track himself.

The album was a hit, producing three singles that topped the R&B charts and reached the Top 10 on the Billboard Hot 100. A source stated that it was one of Motown’s best-selling albums to date. (Smithsonian)

Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology) assesses the state of the world, asking, “How much more abuse from man can she stand?” The earth had changed, and man was responsible.

Inner City Blues (Makes me wanna holler) addresses unemployment, inflation, and the impact of the war. “Trigger happy policing”, he sings. “Panic is spreading.”

The artist behind the cover art, James “Jim” Hendin, passed away this year (2025). In a quote for the Motown museum, Hendin recalled, “The cover shots were the last ones taken...Marvin went out into his backyard, and as I clicked away, it began to snow. That drizzle added everything to the shots. Luck, or something stronger, was with us that day.”

Hendin also photographed other Motown artists, producing some of the most iconic album artwork of the day.

To close, in preparing for this lecture, I stumbled on “What’s Going On: Motown Records Presents Black History Month,” a Spotify and Apple playlist by Motown Records featuring Gaye’s work alongside other artists. Badu, Lil Baby, Stevie Wonder, Quavo…

The artwork is a collage of literal interpretations of the historical moment. The music is a mixed bag. I’m not sure if it was handselected or generated based on similarity. (Spotify does that). Still, I like the idea of bringing Gaye’s work into conversation with pieces from the 21st century. It is lineage.

Like What’s Going On, the art discussed here interacts with history and makes it. Art and history speak to each other. They are molded by each other.

There was a moment last night that encouraged me. By the time we got to Black Panther Newspaper art, the room was actively participating in the discussion. We settled on the image of Ford on puppet strings. I said, “I don’t mean to be presentist but…”

“Say it,” someone said from across the room.

“Ok. I’d be curious how this could be remade in our world in 2025 in the way that Saturn Devouring One of His Sons was remade into an anti-Vietnam poster.“

I’m learning to be firmer and more confident in myself. This feels like the first step in that.

On a human level, I am inspired again by Gaye’s determination to release this record. I am inspired by his conviction and sense of purpose. Marvin Gaye didn’t solve the crises of his time, but he gave them shape and sound. That was not unlike Don Drumm’s steel sculptures, or Emory Douglas’s artwork.

I am excited for future conversations that center on history and art—and that help pave the way for the world we want to create.

Next time…

If you can make it to the next one, I’d love to see you there. I think I’ll talk about some movie posters from the 50s that I found at an archive on campus. Take a look at this one, called “Quadroon.” (Yikes.)

Someone in attendance last night suggested I lecture on the history of Black Horror. You don’t have to ask me twice! That will pair nicely with this poster.

Sources and Resources

Marvin Gaye’s ‘What’s Going On’ Is as Relevant Today as It Was in 1971 By Tyina Steptoe

Kent State University

Jackson State University

Art by Robert Rauschenberg

TC Cannon, Wounded Knee posters

Emory Douglas, Black Panther newspaper art

Don Drumm, Solar Totem #1 and Bridge Over Troubled Waters