The first time I heard about Southern Nazarene University (SNU), my uncle Lionel stood in the kitchen of our family home in Camalote, Belize and told me to apply. He pitched his alma mater as a great way to live out the purpose-driven lifestyle I’d hoped to lead. There were chapel services every week, Christian community building opportunities, and accountability. Our family had attended Nazarene churches in Belize for decades so the denomination was familiar enough to me. Nevermind that Bethany, Oklahoma, the sleepy college town that SNU was nested in, had been a Sundown Town, SNU was the only college I applied to. It wasn’t until I saw the firestorm of racial reckoning unleashed by the Ferguson Uprising that I really learned about the impact of my uncle Lionel on the history of SNU. Still, my Black experience at SNU was different from his. In this post I hope to write the article that I wanted to write while still an undergraduate in 2016, sharing memories, histories, and the names of the faculty and students at SNU who contributed to a long and messy history of racial equity on campus.

I was at SNU from 2013-2017. My first year in college was really difficult. I spent nights alone in the prayer chapel crying for my family, community, and some sense of familiarity. Everything felt foreign to me. I did the best I could to fit in on campus. I learned to two-step at the annual Southern Supper and line danced in campus parking lots. I bought boots and started wearing oversized t-shirts and nike shorts. By my sophomore year, I started to feel more at home. I’d signed up to be an RA and built a community of my own within the bubble that was Bethany. I was young and hopeful and my personal racial identity was never a question to me, and why would it be at SNU? Why would race be an issue at a Christian school, where we were all equal in the sight of God?

I don’t remember the exact first time I thought about race on campus. It might have been when I heard a friend's family member use the N- word in relation to the Black Lives Matter or when a white football player referred to the “blackies” he was competing against in intramural dodgeball. It might have been the time, when driving down the road at the center of campus, I saw a large Confederate flag hanging in the window of a first-floor dorm room in the building that I RA-ed in.

By 2016, it was impossible to avoid. In the early months of the year, the outcry for racial equity and the need for a safe student culture for all students erupted. It began when a white student leader painted himself black to ask another student to a dance. The two stood smiling, holding a poster with the words, “I know you only date Black guys but..” in front of the all-girls dorm on campus. Behind the dorm was Bethany First Church of the Nazarene, technically off-campus, but a cornerstone of Bethany and the home church of many SNU faculty and staff. The image was posted on social media and then recirculated.

Students who recognized this as offensive organized what to do next in snapchat and groupme threads, text conversations, and public spaces on campus. The mood on campus was tense. Days passed and the administration said nothing. The chaplain also said nothing. It was the era of public cancellation so the decision of SNU to keep that student on payroll and in a position of leadership didn’t sit well with many of us then. It felt like SNU chose that student’s mental wellbeing over advocating for the wellbeing of students of color, specifically Black students on campus.

I’d recently completed my first year of research on the impact of petitioning on 19th century protest movements and at some point brought it up to fellow students and sympathetic professors. Someone suggested Change.org. Students and alumni like Olivia Chapman, Deanne Brodie Mends, Jade Overstreet, Taylor Durham, KJ Breckenridge, and Anthony Bryant said we had to do something. With the support of professors and staff members like Jocelyn Bullock, Kim Rosefeld, Michelle Bowie, and Jim Smith, we drafted the petition. On February 22, 2016 we hit publish. Administration remained silent for weeks, even as our petition gained traction in alumni groups and on campus.

One night, a group of us gathered to discuss what else we could do to raise awareness and possibly force the administration to acknowledge the environment that made a student wearing blackface seem appropriate. We met in the newly renovated coffee shop portion of the library that was open to students after the coffee shop closed. I don’t remember there being more than 20 of us - Black students and a few white allies- standing around a large table. (Congregating in this space was not unusual for this part of the library.) In passing, one person suggested a walkout during a chapel service. Another suggested calling the NAACP. Someone suggested a library sit-in. Before our discussion could even begin, however, a senior librarian walked into the room and told us to disperse. The rest of the library remained open and other students were allowed to remain in the space, but even after showing our student IDs, we were instructed to leave. I still do not know their rationale. (Alexa, play Syl Johnson's "Is it because I'm Black.”)

In the weeks that followed, several students were invited to meet with the school president and a sort-of-plan was developed to invest in the Multicultural Student Organization. We also drafted a post called “Why We Care” in a public appeal for better conditions for Black people, people of color, and LGBTQ folks on campus. We hoped this, if anything, would tug at the Christian heartstrings of our community. By late spring, I was exhausted and frustrated at the lack of effort on the part of a school that I, up until then, believed in. After telling her about my family’s history at SNU, my academic advisor suggested I spend some time in the school archive and draft a history of the school for the newspaper. I was told to send the draft of my article to someone on staff to get their approval before sending it to the newspaper editor. That staff member suggested I remove several condemning phrases and statements before publication.

Nearly 10 years later, during Black History Month, I decided to revisit that same article. I've made some revisions, removed certain sections, and added reflections I wish I had included at the time. While not everyone in my family was pleased with the original piece, the histories of my grand uncles and myself are deeply intertwined with Southern Nazarene University. I think that is reason enough to reflect.

2016 Publication Timeline

February 22: Change.org petition is created to gather support for antiracism action on campus (https://www.change.org/p/administration-of-southern-nazarene-university-it-is-time-to-acknowledge-that-racism-is-an-issue)

March 3 : Why We Care Medium Post by SNU students

April 2: Echo Newspaper publication of a History of Diversity at SNU

To gain a deeper understanding of diversity at Southern Nazarene University and within the Nazarene Church over the years, I turned to Corbin Taggart, Director of the Fred Floyd Archives. He pointed me to a wealth of resources in the library and archives, including yearbooks, newspapers, and manuals that might answer several of my questions about SNU’s complicated racial history. I started in the 1960s, a period I knew saw the first Black students on campus (who coincidentally were my great uncles- more on that later.)

The 1960s were a period of intense social and political tension, with civil rights movements for African Americans, Chicanos, Native Americans, women, and the LGBTQ community taking center stage in national discussions. Students organized to protest injustice in schools, transportation, and the Vietnam War. This timeframe seemed like a strong starting point, but I needed more context. I expanded my focus to the 1950s and 1970s. As a result, this piece examines primary source materials from the Fred Floyd archives (1950–1975) alongside articles from Didache: Faithful Teaching, a peer-reviewed Nazarene journal.

In 1965, Southern Nazarene University (SNU), then known as Bethany Nazarene College, found itself navigating the shifting landscape of federal civil rights regulations. Like many other institutions of higher education that received funding or financial assistance from the Atomic Energy Commission—a program sponsored by the federal government—the college was compelled to reassess and adjust its policies to ensure compliance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Title VI explicitly prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance, stating:

“No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Recognizing the potential consequences of noncompliance, including the loss of federal funding, Bethany Nazarene College swiftly took steps to revise policies that could be perceived as discriminatory. This period marked a crucial moment in the institution’s history, reflecting broader national efforts to dismantle segregation and promote greater inclusivity in higher education. While some changes were likely implemented as a direct response to federal mandates, they also signified a growing awareness of the need for racial equity within religious and academic communities.

A record of this compliance is documented in a report titled "Assurance of Compliance with the Atomic Energy Commission Regulation Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964," dated September 1, 1965. Signed by President Roy Cantrell, this document affirmed that Bethany Nazarene College (BNC) did not engage in discriminatory distribution of federal funds or scholarships. However, compliance alone did not mean the issue was settled—just days earlier, on August 26, 1965, Deputy Assistant Manager for Administration W.R. McCauley Jr. of the United States Atomic Energy Commission had sent a letter reminding the college of its obligations under Title VI.

By all official accounts, the institution adhered to the requirements of the Civil Rights Act. My own family’s reflections on BNC and the city of Bethany, Oklahoma paint a different story. Nevertheless, despite this compliance, minority students simply did not attend the school in significant numbers—a reality that raises questions about broader social, cultural, or institutional factors influencing enrollment patterns at the time.

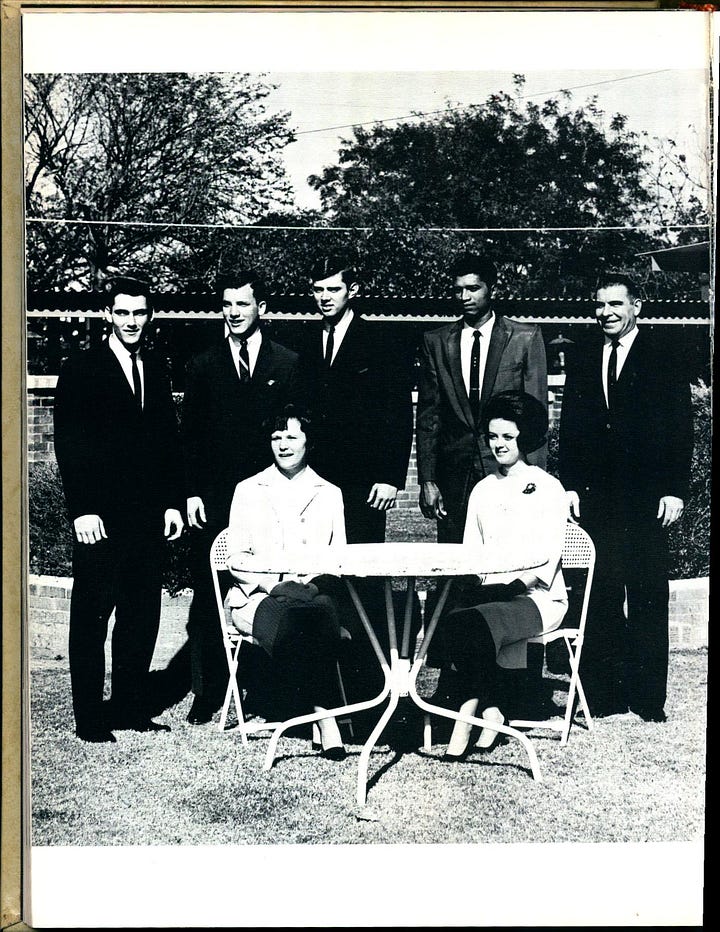

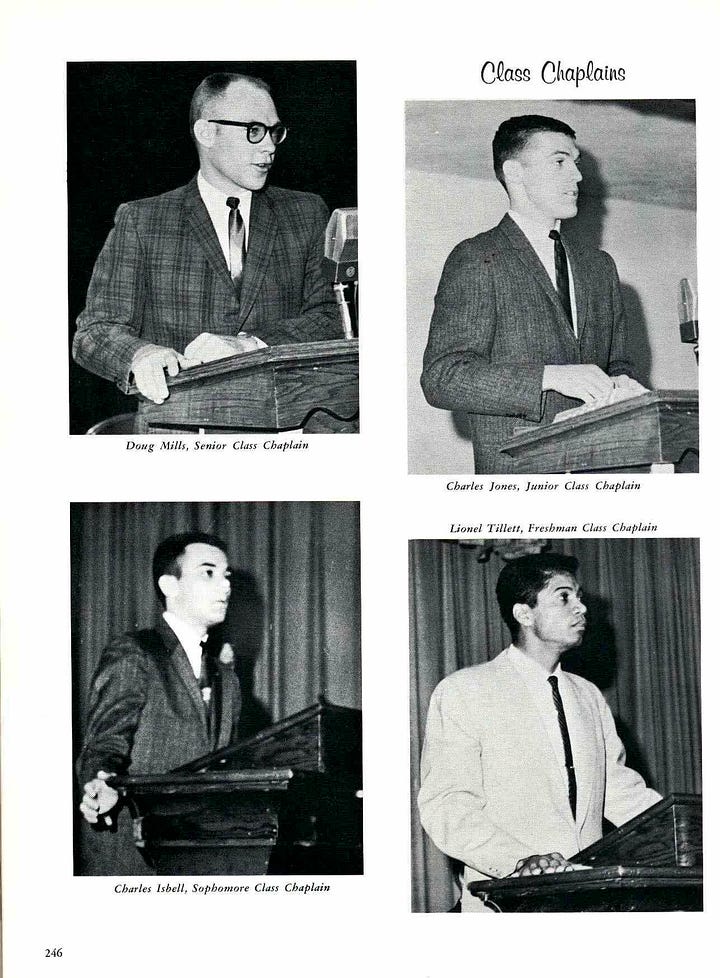

Although students of color made up only a small fraction of the student body, their presence on campus was notable. Among them were brothers Kenneth (Ken) and Lionel Tillett from British Honduras (now Belize), who were deeply involved in campus life. Lionel, an English major, served as class chaplain—a role equivalent to a campus ministries SGA officer—throughout his college years. His academic excellence and leadership earned him recognition in both the yearbook and the student newspaper’s Who’s Who section. Ken, meanwhile, played a significant role in student activism as president of SCOPE, a politically engaged student organization focused on international relations. SCOPE aimed to "contribute to the advancement of world peace, based on justice and freedom" (1967 Arrow, p. 284), reflecting a growing awareness of global issues among students.

Other minority students were also engaged in campus life, though their numbers remained low. Compliance reports submitted to the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, which monitored BNC’s adherence to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, provide insight into the demographics of the student body. In 1964, out of 964 full-time undergraduate students, only 23 were identified as students of color: two classified as "Negro," six as "American Indian," none as "Oriental," and 15 as "Spanish Surnamed American." By 1972, this number had increased only slightly to 25: five "American Indian," six "Negro," none "Oriental," and 14 "Spanish Surnamed American." This presents the great paradox of compliance—while BNC met federal requirements, systemic or cultural barriers may have continued to shape enrollment patterns and student experiences on campus.

One of the most troubling aspects of the university’s history was the use of the team name “Red Skins” for nearly a century, a term now widely recognized as a racial slur against Native Americans. Oklahoma history is Native American history. The land formerly known as Indian territory carries a rich history of Native American cultural expression and excellence. It is also clear that for as long as Native people have been in Oklahoma, the state has undervalued their contributions. In 2016, Native students were members of student government, athletic teams, and Resident Advisors, however, very few people of Indigenous descent were employed by the university as faculty or in positions of leadership on campus.

In 1954, members of the senior class, accompanied by guests and a faculty advisor, attended a banquet set against the backdrop of an old colonial mansion. As part of the evening’s entertainment, members of the student government performed in blackface to the sounds of what was described as “appropriate Negro folk music.” The performances included servers—also in blackface—singing Carry Me Back to Ole Virginie, a student impersonating a “colored waiter” while singing Ole Man River, and a faculty advisor imitating Al Jolson in a rendition of Mammy. A photo of the Senior Plantation banquet depicts a number of students wearing black paint posing for the yearbook. The caption reads “Chicken served ‘Southern’ style by ‘Suhs an’ Missis’ at Senior Plantation banquet”.

A decade later, in 1964, similar racial insensitivity was on display during the student government campaign season. Several students covered themselves in what appears to be black paint as part of their campaign performances, reinforcing the persistence of racist imagery and stereotypes on campus (1964 Yearbook, p. 303). These instances illustrate how racial caricatures and exclusionary traditions were not only tolerated but actively participated in by both students and faculty well into the 1960s. It also suggests how systemic racism operated within the university’s history, shaping both official symbols and student culture.

BNC was not alone in attempting to grapple with integration. By the 1960s, during the height of the Civil Rights Movement, the Nazarene Church had intensified its efforts to recruit African American pastors to lead congregations in predominantly Black communities. This was part of a broader push by religious institutions to navigate the racial tensions of the era while expanding their reach. One such effort was the establishment of the Nazarene Bible Institute in 1948, designed to provide theological education and pastoral training specifically for African American ministers. However, it was not until 1954—just as the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional—that R.W. Cunningham became the first African American appointed as president of the school.

This appointment was a response to the growing number of African American Nazarene churches, which, for a decade, were organized under a segregated administrative structure initially known as the Colored District (CD) before being renamed the Gulf Central District. Formed during the General Assembly, the CD was intended to provide "closer supervision and assistance" to Black congregations. This structure mirrored the broader racial segregation of the time, in which many religious denominations maintained separate governing bodies for Black and white members, reflecting both an attempt at inclusion and a reinforcement of racial division.

2016 Conclusion- In conclusion, all I have to say is this. This semester, I’ve heard that the conversation about diversity is “making something out of nothing” or “it wasn’t an issue until you made it an issue.” However, when we reflect on history, it seems the institution was acting within society’s racial expectations as opposed to aiming for better. Personally, in my time here, I would hate to see SNU be guilty of the same things.

2025 Conclusion- I’m completing my PhD in U.S. History this year, and I often find myself reflecting on my time at SNU. I wouldn’t be where I am without my Uncle Lionel’s encouragement to attend, the support of the SNU McNair Program—a federally funded initiative for students from underrepresented backgrounds—or the voices of fellow students who pushed for a better educational environment for us and those who would come after. Even the unusual experiences, like two-stepping in barns and parking lots, shaped my journey in unexpected ways.

What strikes me most, though, is whether time, independent of concrete action, can change an institution or the culture of a community. Could the legacy of Southern Supper, the welcome dinner for new students on campus that taught me how to two-step, also be a legacy of the Plantation Banquet decades earlier that saw students and faculty in blackface? Could the changing of the mascot from a racial slur, to the Crimson Storm, increase the comfort of Indigenous students on campus? Since my graduation, a number of enrolled students and alumni have reached out about other racially insensitive issues on campus and I worry for the next generation of students. My great uncles Lionel and Ken were some of the first Black students on campus. Both paved the way for more Black students, myself included, to attend the school, learn, and give back to their communities. In this way, both the failures at building a true Christ-centered community in addition to racial diversity, are central to the history of SNU.

Since I graduated, SNU created Intercultural Learning and Engagement to promote differences of experiences and uplift “intercultural people with diverse intersections of identity.” They have also shared a diversity statement. It reads:

Southern Nazarene University values each person created in the image of God, therefore, we also desire to be a community that reflects representation of diversity. We care about inclusion and equity through the refining of our character, the way we create culture, and the way we serve Christ. Our University values reconciliation through God’s love.

An earlier version of this story was published in April 2016, in print and digital, through The Echo, the student-run newspaper at Southern Nazarene University. That version is available here.

References

Fred Floyd Archives

Arrow. Fred Floyd Archives. (yearbook, 1967) p. 84,180, 255, 284.

Arrow.. Fred Floyd Archives.(yearbook, 1964) p. 176, 246, 303.

“Assurance of Compliance with the Atomic Energy Commission Regulation Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” Fred Floyd Archives. (Form, 1964)

“Negro Students Drop-Out Less.” Reveille Echo. (Friday, November 25, 1966. P. 10 )

“Senior Class ‘Visits’ Southern Plantation.” Reveille Echo. Friday, November 20, 1953. p. 60.

Winstead, Brandon. “‘Evangelize the Negro’: Segregation, Power and Evangelization Within the Church of the Nazarene’s Gulf Central District, 1953-1969”.Via http://didache.nazarene.org/

“W.R. McCauley Jr.,“Letter from United States Atomic Energy Commission.” Fred Floyd Archives. (letter, August 26, 1965. )