This Week In Academe: Nahua Intellectualism in the Florentine Codex, the Symbolic Violence of Names, A History of Horror Cinema

October 13-18

Thanks for returning to the second edition of This Week in Academe. I started this project to stay grounded in meaningful scholarship, and I’m finding that each week brings new intersections—Indigenous science and theory, colonial statecraft through names, and even the politics of horror cinema. Here’s what I’ve been learning across the disciplines this week.

10/17: Nahua Intellectualism in the Florentine Codex

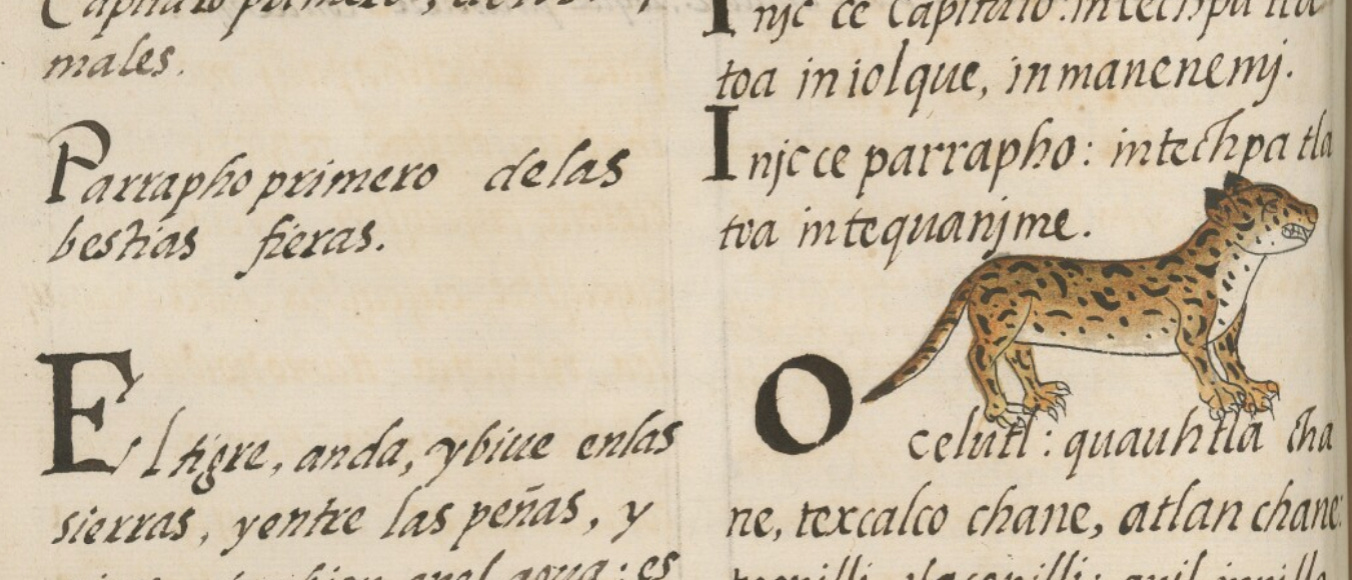

I visited campus for a talk by my mentor, Dr. Kelly McDonough, on the Indigenous intellectualism of Book 11 of the Florentine Codex. Her presentation offered a fresh, intentional reading of this 16th-century Nahua-Spanish source, often mined but less often listened to on its own terms.

Her recent book, Indigenous Science and Technology: Nahuas and the World Around Them, continues this argument, showing how Indigenous knowledge-making is both analytic and theorized.

She argued that Nahua ethological knowledge in particular can tell scholars a lot about the scientific practices of Indigenous communities before interaction with the Spanish. One of the most striking elements of the presentation came when McDonough discussed the ways Nahua scholars gathered information based on bird calls.

For example (this is a paraphrase), some birds, as noted in the codex, were said to predict the weather. When a particular bird called or flew away from its nest, it could mean rain was on the horizon. In Kelly’s words, “Nahua people heard the weather change before experiencing it.” This was an example of embodied relationality, she said—knowledge produced not above or outside the world, but through relationship with it.

This was just one of several ways McDonough traced the intellectual rigor of Book 11, treating it as a site of theory rather than merely ethnography. The talk was hosted by UT’s Environmental History Symposium, organized by Dr. Megan Raby.

Further Reading:

Indigenous Science and Technology: Nahuas and the World Around Them by Kelly McDonough (University of Arizona Press)

10/13: The Symbolic Violence of Names in Algeria

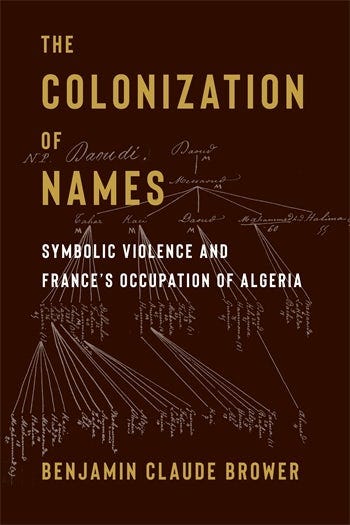

Dr. Benjamin Brower led a discussion of his new book, The Colonization of Names: Symbolic Violence and France’s Occupation of Algeria, as part of the faculty book talk series at the Institute for Historical Studies.

Much of the historiography of naming is grounded in Black and Indigenous studies, exploring the impact of naming on Indigenous landscapes, students in boarding schools, or the names and surnames of enslaved people.

In French-occupied Algeria, naming emerged through a bureaucratic system of vital records—l’état civil—used to track births, marriages, deaths, and property sales. Arabic names were forcibly shortened, standardized, or misspelled to fit French bureaucratic categories. This was linguistic dispossession.

Brower calls the response “onomastic decolonization,” a process through which Algerians seek to restore family histories, repair archival absence, and reclaim names altered by colonial power. He pointed to work by comedian Mohamed Fellag, who critiques French naming practices through satire grounded in Algerian memory and humor.

Links:

The Colonization of Names: Symbolic Violence and France’s Occupation of Algeria by Benjamin Claude Brower(Columbia University Press)

10/16: Behind the Frame - A History of Horror Cinema

Second time’s the charm! This week I led a film and history discussion at Riches Art Gallery, exploring the visual evolution of horror cinema through posters and cultural context. (I may expand this into a full essay soon—stay tuned.)

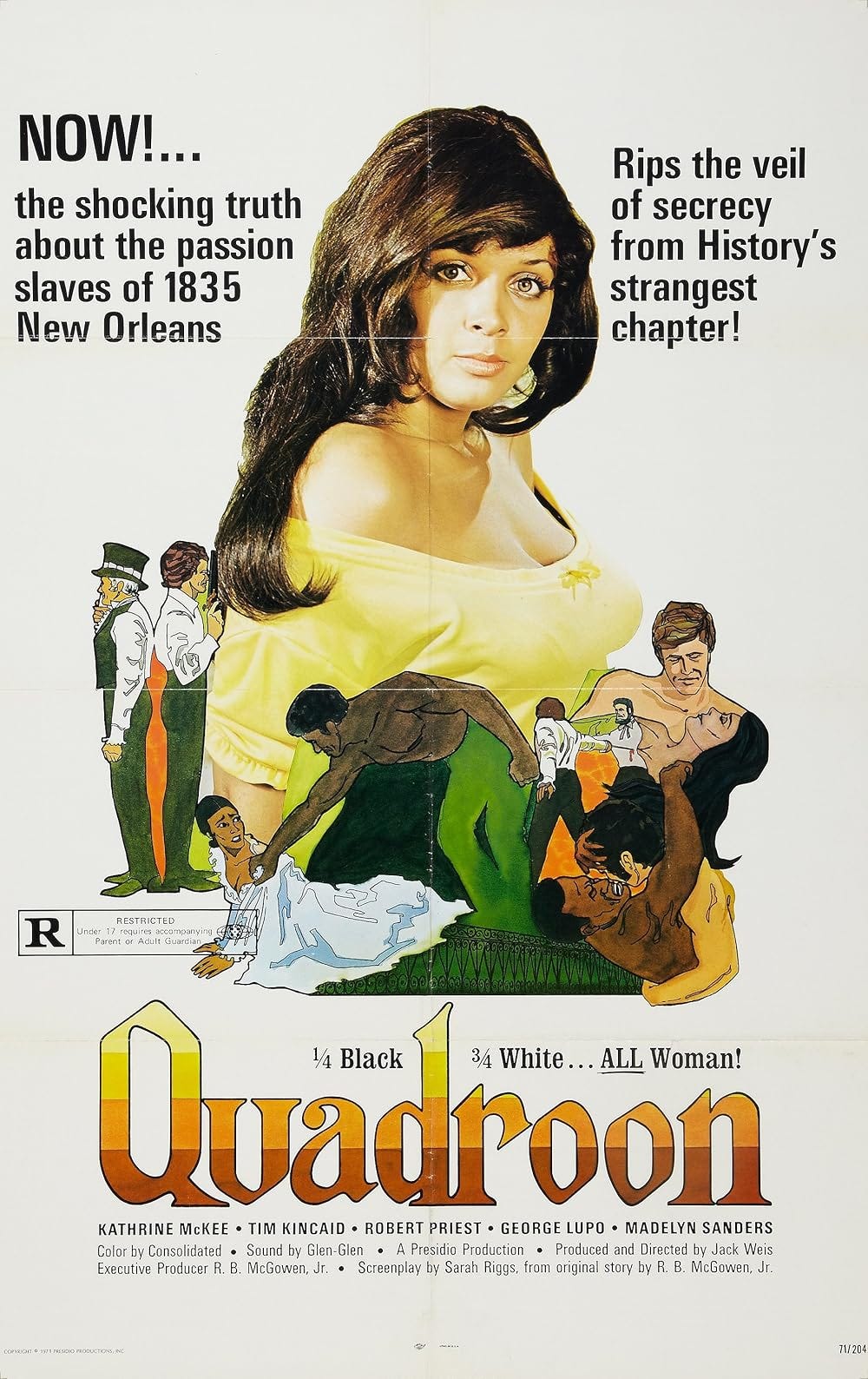

The idea came while browsing the Harry Ransom Center’s digital film poster collection, where I stumbled upon a poster for a 1971 film called Quadroon. The film takes the New Orleans myth of “quadroon balls” and runs with it as historical truth.

Historians have long shown this to be a racialized fantasy that romanticized sexual exploitation and obscured the violence of enslavement in Louisiana. As historian Emily Clark notes:

The myth that grew up around quadroon balls, described vividly in newspaper and traveler’s accounts of the day, was the origin of the city’s first sexual tourism industry and eventually involved bringing women here from other cities… (Read more via Tulane News.)

This encounter raised a question that shaped the rest of the talk: how does horror—as a genre—evolve when we confront historical horror tied to race, gender, and power?This is the thread connecting early exploitation films to modern racial horror like Get Out, Us, Nope, and Sinners.

Further Reading:

Slide Deck (Canva)

Historian Unmasks Quadroon Myth (Tulane)

News…